"I want to capture the personal stories coming from people who experienced these places"

The Fingers interview with GayBarchives.com's Art Smith on documenting historic hubs of LGBTQ+ nightlife before they disappear

Today I’ve got an interview with Art Smith, the proprietor of GayBarchives.com, an online repository of logos from gay and lesbian bars that have closed. I first crossed paths with Smith in January of this year, when he DM’d me about a column I’d published in Charleston’s local newspaper about one historian’s efforts to preserve gay and lesbian bar history in the region. From there, we got to emailing a bit, and I wound up interviewing him in March for this feature I published at VinePair this June about various gay and lesbian bar archivists around the country.

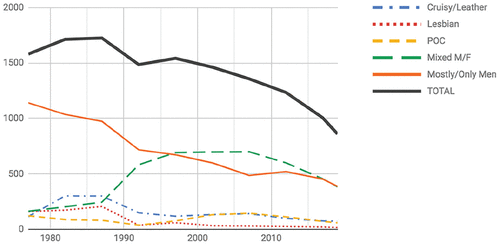

Their work is urgent: dedicated gay and lesbian bars in the US have been on the wane for decades, and as you might’ve guessed, the pandemic did not help. As these once-vibrant third places close, the communities fostered there disperse, and their cultural footprints tend to quickly disappear, unless somebody goes through the effort to preserve them.

Smith is one of those somebodies. The semi-retired amateur archivist, former nightlife publisher, and self-avowed “card-holding member of the gay community” had previously done some research and design work for one Atlanta bar, but kicked his project into high gear after the pandemic robbed him of regular marketing work. Stuck inside with nowhere to be, Smith spent his lockdown tracking down the names, addresses, backstories, and logos of some 1,300 gay and lesbian bars across the country. “I spent quite a bit of time on it,” he told me, laughing. “I would say now it’s probably down to about 20 hours a week.”

Eventually, Smith plans to write a book to catalog all the information he’s turned up, but for now, a lot of it is available on his site, where you can also buy t-shirts and stickers to help underwrite the project. (The individual pages that pertain to each state’s curated shop are where you’ll find info about each individual bar; it’s a little disorienting but click around and you’ll figure it out.) Since we spoke, he’s also begun publishing video interviews with LGBTQ+ nightlife figures to his YouTube channel; you can also download those interviews as podcasts here.

One thing that I really appreciate about the GayBarchives project is how it harkens back to a simpler internet, before the rise of social media platforms and “the attention economy” and all the attendant horrors, when people who were passionate about something—like Smith is about gay and lesbian bar logos—simply logged on and built little online shrines to that thing, just ‘cause.

“I've always been like a nerd when it comes to books and information,” Smith told me when I asked about his motivation for the work. “Once the project started going, it really kind of opened my mind to all of the information that potentially could be dug up out there that wasn’t easy to find.”

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed, and was conducted in March 2021. For a complete archive of Fingers interviews, click here.

Meet Art Smith, creator of GayBarchives.com

Dave Infante, Fingers: Thanks for getting on the phone, Art. How long have you been doing the Gay Barchives project?

Art Smith, GayBarchives.com: So the gay bar archiving project kind of got off to a slow start at the end of of 2019. I did one bar from my past, at the request of the owners, who were the Vara family. They owned Backstreet in Atlanta. I made a commemorative shirt for them and researched some of their history. The next couple of months, I did a few more. And then when COVID hit in March of last year, I kind of kicked the project into high gear because I had a lot of extra free time, and not a lot of places you could go.

Since then, in the last 12 months, I've archived over 1,300 gay bars, most of them gone for years, from all across the country, 49 states. And some in Canada, and a couple in Europe. It is a lot of work.

Yeah, I can imagine. How much time do you spend on this per week?

Well, during the heavy lockdown era, when everything was pretty much closed down, I was spending probably 10 or 12 hours a day.

Whoa.

It was a full-time occupation. I had been doing small business marketing and social media management, and a lot of that [work] dried up. So initially, the first four or five months [of the pandemic], I spent quite a bit of time on it. I would say now is probably down to about 20 hours a week.

That’s still quite a bit.

It's kind of like the tumbleweed effect. As I’m moving along, I’ve started picking up tidbits. There's probably at least another 700 or 800 bars that I haven't really tackled yet. I know the names I know the city they were in, I may know the approximate timeframe [they operated in.] But I haven't completed the research on them. Now, it's a little bit easier. In the beginning, you were trying to find everything out. I mean, how many bars can you think of, from your past? But as I started talking about it online, through Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter, I started getting more and more people to contribute memories and information, names of their favorite bars, and I started tracking them down one at a time.

Has it just been you the whole time? Do you have anyone helping you?

Not really. I get some assistance from a close friend of mine, Dick Woelfle, who operates Channel125.com, which is an online gay video site that's been around for over 20 years. He worked with me on some of the video aspect of it. For instance, right now if you go to my website, there's a video slideshow that has roughly 1,300 bar logos in it. He compiled that for me.

What does the typical process of documenting and archiving these bars look like?

So usually it starts with finding out what the bars are, which bar I’m looking for. Then I go online just like anybody else does, on Google, and I'll find various ways of typing in the name of the bar. For instance, the first one was Backstreet Atlanta. So I put in [search terms like] “backstreet,” “Atlanta, Georgia,” “gay bar,” history,” and I started searching. Once you find an article, very often, that article will lead you to others because they'll mention [details like] the name of the owner, the actual street address, a celebrated performer who was there, a rival bar that was across town.

So I start collecting that information on index cards, and if I can capture an image online, I will put it in a folder on my computer. Then, when I'm ready to tackle that particular bar, I'll pull all those folders out, receive the information, write a description of the basics of the bar, and I will try to digitally recreate or reconstruct a logo or something similar to it. People react to visual elements as much as they do the name of the bar, so I use the logo to kind of spark the fire to get people to remember these bars and to understand how they presented themselves.

Yeah, I mean, one of the things that really caught my eye about your project in particular is how colorful and compelling these logos are.

If you go back into the gay bar scenes from the ‘60s, the ‘70s, even the ‘80s, [the contemporary media] was predominantly underground printing. You know, it was a small, local publications, and they were generally printed only in black and white. So even if the bar actually used color in their logo, you wouldn't necessarily know it. They weren’t publishing in mainstream [outlets.] It’s not like they were on the cover of TIME Magazine. It was like, you know, the Pittsburgh Gay Press. I mean, I published magazines back in the ‘80s as well, gay magazines, and even when you did use color, generally, it was spot color. So you only have one color print, and maybe one accent color throughout the entire publication, other than possibly the cover.

So, for some of [the archived logos] I did add color to make the image a little bit more appealing or to reflect the name. You know if the bar had a name like Blue Parrot, there's blue in the logo. With a logo called the Red Door, there’s red, and so on.

I was looking through some of the logos you’ve found. It seems like certain motifs keep coming up, regardless of where the bars were located.

There were two reasons for that. One reason is that, especially in the early days pre-Stonewall, it was almost codified. So there were a lot of bars in the ‘50s and ‘60s that used the combination of a color and a bird. And the reason for that was so that when people were traveling—if you were a gay man from, say, Los Angeles and you happen to find yourself in Dallas—you would see a bar name that was the Red Falcon and it would kind of be a flag to you. ‘Hey, that's probably a gay bar.’ So, because there wasn't the widespread information that we have now with the Internet, it was a way of being kind of subtle and not saying “gay bar.”

Another reason was because, like The Eagle in New York, well it used to be called The Eagle’s Nest, and it was known for a particular genre. It was known as a “man's man's” bar. You didn't go in there in a suit and tie or a preppy outfit. It was a kind of motorcycle gang, Levi and leather, that kind of thing. So once people started talking about that in other cities, they would say ‘Hey, we should have a bar like the Eagle's Nest in Chicago,’ for example. They were not ever connected, there is no chain of Eagles. They're all individually owned and operated. They never had any organizational concept behind them.

That’s so interesting!

You'll notice I do have one design, a collective design I call the Convocation of Eagles. Because the word “convocation” is what you call a flock of eagles. A group of flamingos is called a “flamboyance.” A group of eagles is called a “convocation.”

I put together a design that incorporates the defunct logos of 13 Eagles, including the Eagle’s Nest at the top and then 12 other Eagles that used to exist. If you look at those logos, the look of the eagle itself changes dramatically. Some of them are very primitive, while some of them are very detailed and artistic. So, there was no real consistency even in the logo.

In terms of the stickers and the tee shirts, are you using that money to fund GayBarchives.com? How are you funding the project?

It contributes to the project, but I also work for a friend of mine who owns a retail business on Saturdays to supplement a little bit. I'm also at retirement age so I have the good fortune of having some retirement income as well. But I’ve made sure that 50% of the profits from the designs, particularly from Louisiana bars, go to the LGBT+ Archive of Louisiana. The amount of bars that I have documented from the state of Louisiana, right now is about 14 or 15. I’m working on more. Every one of those designs, 50% of the proceeds go to the archive.

I've done that with other nonprofit organizations that are involved in different ways in their communities, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in Atlanta benefited from the first Backstreet design. So there's also the giveback aspect to it.

That leads to my next question: what motivates you. I applaud the work that you do for sure, but it is work. You put so much into this. What energizes you to continue with this project?

I want to capture the personal stories coming from people who experienced these places that can be archived. For instance, In Atlanta, there was an iconic bar owner. She had her first bar, The Rose, which was a lesbian bar. Then she had three bars after that.

She made a big impact on the The Atlanta community. Both as kind of a den mother to the gay community, as a supporter of nonprofit organizations, and as just a personality. I've spoken to her several times recently. She’s 85 years old, and if I don’t catch her on video now, there may not be a chance 10 years from now to do it. To me, that's an important part of capturing this history, so that young people can see what happened before. I've always been like a nerd when it comes to books and information. Once the project started going, it really kind of opened my mind to all of the information that potentially could be dug up out there that wasn’t easy to find.

One of the most intriguing stories I had discovered recently was a bar in New Orleans, which was called the Upstairs Lounge. It was a tiny second-floor bar with a maximum capacity of about 100 people. On the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, they had a group of about 60 people up there, celebrating the memory of Stonewall. A lot of people from the local gay church were there. In the middle of the afternoon, somebody threw a firebomb against the building and killed 32 people who were trapped up in the bar.

Oh my god.

That was the grimmest gay bar tragedy prior to Pulse [Nightclub, the site of a 2016 shooting that left 49 people dead.] But if you think about it, for 43 years, from when that happened until when Pulse happened, hardly anyone knew about it.

I have to admit, I’d never heard of Upstairs Lounge until you just mentioned it.

Now, if you go online and you type in “Upstairs Lounge fire” and “New Orleans,” you’ll find maybe half a dozen articles. But still, it is not documented in a way that most people would ever find it. So digging up that information, and hearing people say ‘wow I never knew about that,’ that inspires me a little.

Then of course, the messages that I get from people. I get comments, I have a group page for the GayBarchives Project on Facebook. I get comments from people all the time. I had somebody today who sent me a message saying, “I’m a big fan of what you're doing. Thank you so much for all this work that you've put into it. You know, I don't wear t-shirts or do any of that but I would love to be able to support your project. Can I send you a donation to help show my support for your work?” And I said I don't expect that it’s not set up as a nonprofit or anything. But he said “No, I want to show my support for you,” and in 15 minutes there was a couple $100 in my account. So, of course, that adds to [my motivation] as well, when people feel that it’s so important to them that they volunteer to contribute to the project as well.

What's the biggest challenge in front of you right now? Is it financial?

Not really. The t-shirts do bring in some money, some retirement income helps, and the other income helps. The biggest obstacle is getting the information about the bars. It's about having interactions with people so they can tell me ‘Yeah, I lived in Des Moines, Iowa in 1968, and there was this bar there, here's the information.”

And another big challenge is just finding the logos. If you think about it, we’re talking about years when people were printing in these underground publications that may, in many cases, have only lasted a year or two, and certainly were never scanned and archived online. Where do you find them? That's been a huge challenge. I’ve probably got at least 100 bars that I could add [to the archive] immediately if I could find some copy of their logo. Some of those bars I've even been to! I just don't remember what the sign looked like 40 years ago.

Where do you find that stuff if it was never scanned? What is your process, at that point?

Through interaction on social media. A lot of it happens from people making comments or posting photographs, which were pretty rare in the scene back then. You have to [remember] this was forty years ago. People did not walk into a nightclub with a camera, especially a gay bar. Now it's in your phone. So everybody has a 1,000 pictures on their Facebook page of what they did last week. But the people who do have pictures, sometimes will have a group shot, that will show a portion of the [bar] logo on a wall above the stage. Or maybe somebody's wearing a t-shirt with the bar logo on it. So you have a kind of a vague idea what it looked like.

There are some archival projects that include logos. There's a pretty big one out of Wisconsin, and another one out of Texas that has archived a number of [gay nightlife] publications. Of course, then the challenge is you go through the publications. So say you’re gonna go look at the 1972 issue of this magazine [for an advertisement from a specific bar.] Maybe now you have an image of a logo, and the address of the bar. But then you have to go and find the rest of the information, because nobody put in their ads ‘we opened in 1958, we closed in 1973.’ So, all that information you have to find elsewhere.

Right, right.

The more you get connected, the more people start to tell you. ‘Look at this source or look at that book.’ There are a couple books online that people have published that have photographs of the old bars and ads and stuff. eBay is another good source. Go to eBay and type in the information about the club you're looking for and [the search term] “memorabilia,” and you’ll find matchbook cover. ‘Cause back then all bars had matches. Particularly gay bars, because the idea was if you went into a gay bar and met somebody, you could take a matchbook and write their name and number inside. Some of them would even have stupid little checkboxes [to indicate] whether or not you would have sex with [the person who gave you the matches.]

Matchbooks were probably the biggest promotional item that a lot of the gay bars used back then. As I uncover those—and of course, people who have matchbooks in any genre, tend to collect hundreds of them—I will just ask them if they can send me some photos of their matchbook collection. You get maybe half a dozen photos, each photo will have 10 or 12 matchbooks in it, and now I’ve got those designs. So it's complicated, but the logos can be found. It just takes time, and you have to start to know where to look.

After 1,300 bars I have a lot of connections. I know people who are doing archiving projects in Pennsylvania, Louisiana, California, and Texas. So you get their connections. So that gives me plenty of ammunition to work from. The last video interview I did was with the guy who owns a bar in Buffalo, New York, called Club Marcela. He’s been there for over 25 years. He’s also owned some other bars in other cities, but because he's been around so long, he knows the people that owned the bars that were open when he first opened, which is between 25 and 30 years ago. So he's connected me with some of them. It just kind of grows and mushrooms.

Yeah, in terms of people who want to help you with your project or send you tips, what's the best way they do that?

The absolute easiest way is to go to GayBarchives.com. If you click on the contact page, it has a direct email option there, it also has links to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Pinterest. There’s even a link to the Gay Barchives Facebook group, which is an interactive group I started about six weeks ago. People post pictures and comments… the video I posted a few days ago has reached over 2,200 people. A lot of the individual posts reach hundreds of people.

We get a lot of feedback and people will add to or change information. We’ll know, as a result, one bar wasn’t really that big; it only had one little dance floor. You kind of get the conversation going so you can tweak the information to be more accurate.